Beyond the Summit: How Three Pillars Led to Our Success on Kilimanjaro

In the summer of 2024, I set out on a deliberate mission: to study firsthand what separates success from struggle at high altitude. I joined a mountaineering seminar on Mt. Rainier and participated in group climbs on Gran Paradiso and Mont Blanc—intentionally choosing teams I didn’t know, where I had no hand in their preparation. I wanted to observe it all: the wins, the breakdowns, the blind spots.

What I gained wasn’t just experience. It was insight. I came away with a framework that has since reshaped how I prepare athletes for the mountains—one we’d go on to use in full during our 2025 Kilimanjaro expedition. That same framework is now guiding our approach to future expeditions, including an upcoming rapid-ascent trek in Peru.

Altitude illness isn’t abstract. Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS), High-Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE), and High-Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE) are real risks, and I’ve seen what happens when even strong athletes show up unprepared. But I’ve also seen what works—when the right systems are in place.

Out of all that fieldwork emerged a clear, practical framework: TAP—Training, Altitude, and Psychology. We built our Kilimanjaro expedition around these three pillars:

- Training – Physical conditioning, technical movement, and fueling strategy

- Altitude – Gradual exposure, smart itinerary design, and science-backed medication use

- Psychology – Personal resilience and intentional group dynamics

And it worked.

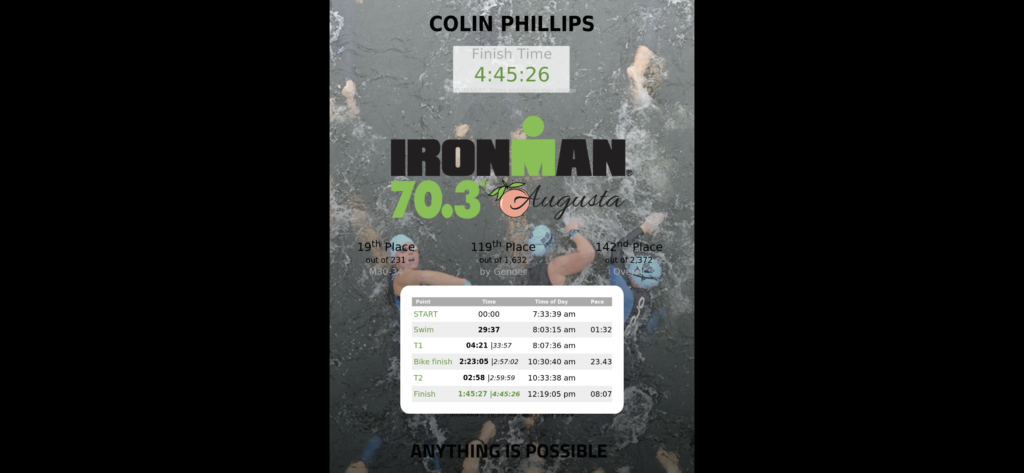

Despite arriving with mild chest colds, we moved efficiently. We completed each day’s trek in half the estimated time, arrived early enough for hot meals and naps, and fully recovered before moving again. On summit day, we reached the top, returned to high camp for lunch, and still descended to Low Mweka—giving us a short, relaxed final day to the gate.

This wasn’t luck. It was execution.

We trained with intention. We planned with discipline. And we climbed as a team.

Why It Matters

If you’re going from low elevation to anything over 8,000 feet in a short window, you’re at real risk for AMS—regardless of how fit or tough you are. Per the CDC and WMS, fitness is not protective, and even living at moderate elevation offers limited defense if you’ve been at sea level recently. The only consistent protection? Proper acclimatization and evidence-based preparation.

Let me walk you through a few key examples that shaped how I prepare myself—and others—for elevation today:

Longs Peak – A Lesson in Fueling at Altitude

Before heading to Mt. Rainier, I planned a warm-up trip to Colorado with several days of backpacking through Rocky Mountain National Park. I knew that spending 3–5 days above 9,000 feet was a smart way to jumpstart acclimatization, and I’d planned accordingly.

What I hadn’t planned for was just how hard it would be to eat.

I camped in the boulder field on Longs Peak at 12,700 ft, having come from sea level just days before. While I didn’t experience Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS)—no headache, nausea, or dizziness—I struggled with mild anorexia, a subtle but common side effect of elevation. I knew this was normal. I had read that mountaineers are advised to bring hyper-palatable foods. But I assumed that my background in endurance sports and military training—where you learn to “shove it in” even when you don’t want to eat—would carry me through.

It didn’t.

For the sake of packability and bear-canister space, I’d chosen lightweight, low-volume dehydrated meals, bars, and trail snacks. But come breakfast before my summit attempt, none of it was appealing. I managed to eat, but not enough to stay properly fueled. I moved at the pace I expected for someone acclimating from sea level, but by the time we descended and the snow started falling near the Keyhole, I felt how underfueled I was. The mental load of “catching up” on calories while moving through dangerous terrain in worsening weather is not something I’d want to repeat.

Lesson Learned: Even without AMS, fueling can be a challenge at altitude. Don’t rely on hunger cues or assume mental toughness will override flavor fatigue. Pack hyper-palatable, calorie-dense foods that you want to eat—even if they’re heavier. “Fast and light” is only smart if it keeps you fueled. I now bring donuts on summit day.

Mt. Rainier – A Lesson in Hydration and Side Effects

Later that month, I climbed Mt. Rainier. This time, my preparation was spot on: a month of backpacking in Colorado and the Pacific Northwest had built my fitness. I’d integrated more real, hyper-palatable foods into my pack—though not quite at the level of my teammates who were happily eating cold pizza at every other meal. Between structured training, on-mountain acclimatization, and improved fueling, I felt strong hauling our alpine packs, loaded with everything from ice axes to snow shovels.

But this climb introduced me to another important variable: open group dynamics.

I didn’t know any of the other climbers beforehand. Over the two-day ascent, one teammate from Texas began noticeably falling behind. It caught my attention—especially given his resume, which included summits like the Grand Teton.

At Camp Muir, we learned the cause: he had been taking acetazolamide, but at full therapeutic diuretic dosage, not the lower preventive dose recommended by the WMS for AMS prevention. His primary care provider had prescribed it without altitude-specific guidance—doubling the dose and failing to warn him about common but harmless side effectslike tingling in the extremities. That, combined with frequent nighttime urination, left him dehydrated, exhausted, and mentally rattled. At high camp, he decided to opt out of the summit attempt.

On our way down the mountain, we were practicing plunge stepping and moving fast. I was on a rope team with our head guide and one other climber, and keeping up with their pace was a real challenge. I couldn’t get my heel planted quickly enough while keeping my toes elevated. If I moved too naturally, my feet angled forward and I started to ski. The alternative—slamming my heel down with a locked knee and full body weight—felt risky, especially if I hit something solid beneath the snow. We were still outpacing the other rope teams, but it was clear I was slowing my own team down.

Afterward, I asked the guide for feedback on the week. He said, “I’ll take you climbing anywhere, but you need to practice your descending so you’re not the one holding the team back from moving as fast—and as safely—as possible down the mountain.” Knowing my main goal on this trip was to understand how to better prepare endurance athletes for alpine environments, he added something that stuck with me: “Everyone trains to go up. They forget to train for coming down.”

I often talk to ultra runners about eccentric loading and the importance of practicing descents but descending on a glacier made it clear—this isn’t just about ice tools or rope skills. It’s about learning how to move in the alpine environment. Even something as basic as walking requires a completely new set of technical skills.

Lesson Learned: Always test altitude medications before a climb. Know the side effects, understand wilderness-recommended dosages, and time your doses to avoid overnight disruptions. Acetazolamide is a powerful tool—when used correctly. But in this case, poor medical guidance and unfamiliarity with the drug’s effects cost an otherwise capable climber his summit attempt.

And perhaps most importantly… learn how to walk. On steep snow and glaciers, even basic movement becomes a technical skill. Downhill matters just as much—if not more—than the climb up.

Gran Paradiso – A Brush with HACE

After learning valuable lessons on Longs Peak and Mt. Rainier, I headed to Europe to take on Mont Blanc, the highest peak in Western Europe. As part of the guided program I’d joined, a check climb on Gran Paradiso—Italy’s highest mountain—was required first.

This time, my training looked a little different. I built my aerobic base through cycling and swimming at home, then spent three weeks backpacking through Scandinavia. I averaged 30,000–40,000 steps per day, climbed 100–200 flights of stairs, and hauled a full camera kit the entire way. I knew this would be a hut-to-hut climb, so my gear load would be about 20% of what I carried on Rainier—a welcome change.

I spent several days at base camp in Chamonix before the climb, using the time to observe group dynamics. I made it a point to learn who had trained, who had real mountain experience, who had faced mentally tough situations before—and who was on what medications. My fitness and fueling were dialed in, and now it was time to manage the human element, because in open group climbs, that can matter just as much.

We drove from Chamonix (3,369 ft) to the trailhead (6,030 ft), then climbed to Refuge Chabod (8,890 ft) in a single day. We slept there before our summit push.

Out of nine climbers, four turned back during the ascent due to fitness, gear issues, or early AMS symptoms. As people dropped out at different times, we gradually lost guides—eventually leaving five climbers with one guide.

That’s when it happened.

The climber behind me shouted, “Come on, [mate]! I can’t keep pulling you up the mountain—I’m not strong enough to climb for us both!” I’d felt repeated tugs on the rope for the past 30 minutes and now I knew why. One teammate was being dragged—literally—up the mountain.

I urged those behind me to stop hauling him and suggested moving him to the front of the rope so the guide could assess him more closely. But the group hesitated and kept towing him along. I turned to the nearest climber and said what had to be said: “The summit isn’t the finish line—it’s the halfway point.” The plan to push him to the top at all costs wasn’t just unrealistic—it was dangerous.

The guide overheard and agreed. He moved the climber to the front to monitor him. That’s when things became undeniable. The young man began stumbling, sliding backward, crying, and speaking incoherently. He was clearly disoriented and no longer able to care for himself—we had to remind him repeatedly to put on his goggles to protect his eyes. The others still encouraged him: “You’re almost there. Just keep going.” They didn’t yet understand how critical the situation had become.

This climber was the fittest and youngest in our group of nine—easily 30 years younger than some of us. And yet, he was the one falling apart. It was clear we were witnessing rapid deterioration, likely the early onset of High-Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE).

After about 10 minutes of him struggling behind the guide, we were hit by wind and snow from the edge of a storm that—unbeknownst to us at the time—was claiming lives on Mont Blanc. We were exposed, cold, and rapidly losing our margin for safety. Every stop for him to argue with the guide about continuing was putting the rest of us at risk.

After two more such stops, the guide made the call: we were turning back. The climber in question finally agreed, in tears.

As we descended, his speech improved. By the time we returned to the hut at 8,890 ft, he was almost completely back to himself. The change was startling.

The next morning over breakfast in Chamonix—before we set off for Mont Blanc—the two climbers who had been pushing him the hardest pulled me aside. They admitted they had been so fixated on reaching the summit, they hadn’t even considered how they were going to get him back down.

Lesson Learned: Stay clear-headed when others aren’t. Be strong enough—mentally and physically—not to get swept up in summit fever. This experience also reinforced the difference between being fit and being prepared. Several climbers who struggled that day were incredibly fit—but they hadn’t trained for the demands of high-altitude mountaineering. They had been working out, not training. That made all the difference. I was objectively less fit—but I had the experience of hauling a load all day, and the mental toughness to stay calm and make hard decisions when it mattered most.

Mont Blanc – Mental Fatigue at Altitude

Just one day after Gran Paradiso, we set our sights on Mont Blanc. The group was already worn down, both physically and mentally. At 14,311 ft, we reached the Vallot Hut, and once again the team splintered—this time due to fatigue and doubt, not altitude illness. Most of the group turned back.

Only three of us pressed on: myself, and the same two climbers who had tried to haul a faltering teammate up Gran Paradiso. We would go on to reach the summit through a brutal windstorm.

This time, I was more prepared in every way. I had packed donuts—despite the house manager at the climbing company gasping in disbelief as I slid them into my pack: “How are you going to keep those from getting smashed?” My answer? “Carefully.” I wasn’t climbing for style points—I was climbing fueled.

I also had a good sense of who would summit. I’d spent the previous few days watching group dynamics, listening to people’s stories, and observing how they moved. The guides had been paying attention too, and ended up grouping climbers on ropes almost exactly how many of us thought they should. That small detail made a big difference.

Fitness wasn’t the issue. Three weeks of backpacking around the Baltics and Scandinavia with camera gear that outweighed my alpine pack had done its job. My base was solid. I wasn’t the strongest or fastest—but I was steady, and I knew what I was doing.

Back at base camp in Chamonix, we finally learned what had contributed to one climber’s dramatic struggles on Gran Paradiso: he’d been wearing technical ice climbing crampons, not mountaineering ones. He had never walked on a glacier before our summit attempt. Each step had him slipping and overexerting—doing nearly double the work as the rest of us just to stay upright.

That night in Chamonix, after hearing his story, three of us with glacier experience gathered the group for a mini skills clinic. We reviewed each other’s crampons, made adjustments, and shared movement tips. It was a subtle but powerful reminder that group dynamics aren’t just about people and personalities—they’re also about gear.

Oh yeah… and learning how to walk. I feel like I’d heard that before.

Lesson Learned: Preparation isn’t just personal—it’s collective. When you’re part of a guided trip, you might assume the guides are checking everyone’s gear and assessing their skills. But that doesn’t always happen. One more key takeaway in group dynamics: assess your teammates before you rope up. Know who you’re tied to—not just in fitness, but in skills, experience, and equipment—even on a guided climb.

After watching so many climbers falter—whether from mental fatigue, gear issues, or altitude—it also hammered home the importance of the CDC and WMS guidance: keep sleeping elevation increases to no more than 1,600 feet per night above 9,000 feet. On both Gran Paradiso and Mont Blanc, our rapid ascent profiles clearly played a role in how many of us struggled.

The final push from the Vallot Hut to the summit was, without question, the toughest thing I’ve ever done. And that experience taught me another crucial lesson: don’t blindly trust the itinerary. Question the pacing set by commercial tours and make sure it aligns with proven acclimatization strategies.

And seriously—learn how to walk. After months of practicing stair descents heel-first, toe-up, and refining my technique on every staircase I could find, it felt like a full-circle moment when the lead guide called out as we descended from the summit: “Like a pro—who taught you how to descend so fast?” – The team on Rainier would be proud.

Putting it Together – The Roof of Africa

After a summer of learning experiences across Longs Peak, Mt. Rainier, Gran Paradiso, and Mont Blanc, I emerged with a clear framework for preparing athletes—and myself—for success at high altitude. Now I was ready to put together my own group and begin helping athletes prepare for high altitude adventures. These lessons became the framework and the foundation for planning our Kilimanjaro climb, and it’s built on three pillars:

- Pillar 1: Training – This includes physical fitness, technical skills, and fueling strategies. It’s not just about being in shape—it’s about training for the specific demands of altitude and alpine movement.

- Pillar 2: Altitude – From pre-trip exposure and acclimatization protocols to proper medication use and smart itinerary design, altitude preparation is where science and planning come together.

- Pillar 3: Psychology – Resilience isn’t optional. Success depends on mental preparation, self-awareness, and understanding group dynamics in unpredictable environments.

These pillars guided every decision we made for Kilimanjaro—from choosing the right route and guiding company to building a team that could execute the plan. But they weren’t born in a classroom. Each one was forged through hard-earned lessons—some personal, some observed—on climbs where things didn’t always go to plan.

Pillar 1: Training – Fitness, Skills & Fueling

Our Kilimanjaro team was built around one core belief: targeted, structured training matters. After watching strong athletes falter on Gran Paradiso and Mont Blanc due to a lack of event-specific preparation, I knew that general fitness alone wouldn’t be enough.

We approached training the same way I coach endurance athletes—through multisport conditioning (swimming, biking, running) paired with rucking under load to simulate mountain fatigue. This hybrid model built not only aerobic capacity and muscular endurance, but also movement confidence, an essential ingredient when facing long days on trail with uneven terrain and elevation gain.

We also tackled fueling head-on. Longs Peak taught me that appetite suppression is real at altitude, and fast-and-light nutrition quickly breaks down when your stomach says no. For Kilimanjaro, nutrition became a priority from day one.

We selected a guiding company that provided three fully cooked meals each day—not just the standard hot breakfast and dinner with a repetitive boxed lunch. We worked with the team in advance to ensure a rotating menu and gave input on preferences before arrival to help keep meals diverse, satisfying, and appetizing throughout the trek. We also packed hyper-palatable, calorie-dense snacks, knowing that having familiar, easy-to-eat food would be essential—especially on summit day.

Our final fueling strategy included a little insider magic: our version of “Sherpa tea.” On previous climbs in Italy and France, I had learned firsthand that sweet, fatty hot drinks can completely change your energy and mindset on a long climb. For Kilimanjaro, we combined hot chocolate with chocolate malt drink powder to create a thick, calorie-dense beverage served at meals. And each day on the trail, we carried a thermos filled with fresh lemon ginger tea, prepared from real ginger and lemons (yes—our chef was that good), and fortified with salt and sugar to keep hydration, electrolytes, and energy steady throughout the day.

We didn’t just train to move—we trained to move with intention.

And we didn’t just pack food—we packed with a purpose to fuel.

Pillar 2: Altitude – Exposure, Medication & Smart Ascending

Having seen the effects of poor acclimatization firsthand—especially the rapid decline of a teammate on Gran Paradiso—altitude strategy became a cornerstone of our Kilimanjaro planning. I knew we couldn’t leave adaptation up to chance.

Altitude Exposure

We began with altitude simulation tents, gradually increasing sleeping elevation in the weeks leading up to departure. The goal wasn’t just to tolerate altitude—it was to begin adapting before we ever stepped on the mountain. We used SpO2 and sleep quality metrics to determine our progression rather than simply ramping up every few nights. Personally, I built my sleeping altitude up to just over 16,000 feet, mirroring the elevation of Kosovo Camp, our high camp.

To simulate summit day, I also performed structured treadmill workouts at up to 19,000 feet of simulated elevation. These sessions mimicked our summit push profile: low intensity, long duration, and a steady grind—all while returning to a sleeping elevation that reflected our high camp. This combination of passive and active exposure helped normalize altitude stress long before we reached Tanzania.

Smart Ascending: Route Selection & Itinerary Design

We selected the eight-day Lemosho Route, known for its gradual profile and high success rate. I specifically avoided faster itineraries like the Marangu or compressed Machame routes. Per CDC and Wilderness Medical Society guidelines, sleeping elevation gains above 9,000 feet should not exceed 500 meters (~1,600 ft) per night, and rest days should be built in if that threshold is surpassed.

The Lemosho Route gave us four full days sleeping between 11,500 and 13,650 feet before moving to high camp on day six. This natural altitude “plateau” aligned perfectly with best practices for acclimatization. In contrast, the classic Marangu Route offers only two nights above 9,000 feet before its summit bid.

We also added a pre-trek rest day in Arusha instead of starting the climb immediately after arriving in-country. This gave us two solid nights of recovery sleep post-flight and ensured we began the trek fresh and hydrated—not jet-lagged and depleted.

Our route choice was reinforced by a sobering reminder just one day after arrival. At breakfast in the hotel, I overheard a man struggling to breathe as he came up the stairs. I later learned he had just returned from a 6-day version of the Machame Route, which had been compressed even further by skipping high camp rest.

He and his daughter had reached Karanga Camp at 13,106 ft on Day 4 and, at the suggestion of their guides, opted to continue straight to the summit rather than setting up at Kosovo Camp (15,978 ft) for a short nap and recovery before a traditional night-time ascent. The guides had pitched the idea as a way to summit midday and “have the mountain to themselves.”

Between Karanga and Kosovo, the father went down hard with severe AMS and signs of High-Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE). He had to wait at high camp while his daughter summited alone. By the time we spoke in Arusha, he was clearly still recovering, though improving now that he was back at low elevation. The difference in outcomes was stark—and a confirmation of what we had agreed on from the beginning: no matter what the guides say, we would move only as fast as our plan required—not faster.

Altitude Medication Strategy

Finally, we implemented a two-tiered medication protocol grounded in CDC and WMS guidance.

Both Marina and I began acetazolamide 24 hours before starting the trek, continuing through our time at altitude. Acetazolamide is recommended for moderate to high-risk AMS scenarios, as it helps accelerate adaptation by stimulating respiration and improving oxygen uptake.

For the summit, we added a dexamethasone protocol beginning 12 hours before our push and continuing through our return to high camp. While dexamethasone doesn’t promote adaptation, it is highly effective at preventing and treating AMS symptoms, particularly in high-risk scenarios like rapid elevation gain or overnight pushes from high camp.

This stacked approach—acetazolamide for steady adaptation, dexamethasone for summit day insurance—was reviewed and approved by my travel medicine doctor. It was designed to maximize adaptation and reduce risk without relying entirely on any one intervention; note there is no guidance from the CDC or WMS on stacking these two medications.

Pillar 3: Psychology – Resilience & Group Dynamics

If there’s one thing I took away from Europe, it’s this: your rope team can make or break your summit.

On Gran Paradiso, I saw a team nearly push past the point of safety due to poor decision-making and a lack of situational awareness. On Mont Blanc, I watched climbers turn back not because of physical limitations—but because of mental fatigue. I learned firsthand that success at altitude isn’t just about physical training—it’s about building a team that knows how to suffer well together.

For Kilimanjaro, we didn’t just train in isolation—we built the team before we hit the trail.

Marina and I trained in different cities—me in New Orleans, her in Washington D.C.—but we stayed connected. We talked regularly about our goals, pacing expectations, gear, logistics, and communication strategies, both on the mountain and with folks back home. We each brought different strengths to the table, and we acknowledged them early. We read trip reports, studied the mountain, reviewed maps together, and even consulted with professional ultra-distance athletes to learn how they mentally prepare for multi-day endurance efforts.

In short, we approached this not just as a climb—but as a shared project. One that required aligned expectations, honest communication, and mutual respect.

And because of that, the mental side clicked.

There were no group meltdowns. No one got caught in summit fever. We moved as a unit, adjusted to each moment, and supported each other with calm energy—even when I gave Marina a chest cold I picked up in New Orleans. We were sick. We were tired. But we were never rattled.

On summit day, we moved steadily, efficiently, and without drama. And in the world of high-altitude trekking, that’s as good as it gets.

Success on the Trail – Where Preparation Met Performance

When we stepped onto the Lemosho trail, we weren’t just hoping for a summit—we were walking in with a plan built on the Three Pillars of High-Altitude Success: structured Training, intentional Altitude strategy, and solid Mental preparation.

And that plan worked.

Despite both of us coming into the climb with mild chest colds, our fitness and acclimatization base allowed us to move efficiently each day—completing every trek in nearly half the estimated time outlined by our tour company. That wasn’t because we were rushing. It was because we’d trained for the specific demands of altitude, we’d built up the ability to move well under load, and we had adapted to elevation long before stepping on the trail.

This time advantage meant we could sleep in most mornings, enjoy a calm and steady start to the day, and still arrive to camp in time for a hot lunch. We had time for post-lunch naps, full recovery windows, and the energy to eat three hot meals every single day—a huge win at altitude where appetite often disappears.

Even on summit day, we moved steadily and efficiently, reaching the top without incident and descending with enough energy to take a mid-morning nap back at high camp, enjoy lunch, and then continue on to Low Mweka Camp instead of stopping at the higher site. That gave us a shorter, more relaxed final day to the park gate—and a chance to really soak in what we’d accomplished.

The ability to move efficiently, sleep deeply, and fuel consistently all came from the groundwork laid before the climb. Training gave us the physical capacity. Altitude planning ensured we could adapt and stay ahead of AMS. And our shared mental framework helped us navigate challenges with calm and confidence—never getting rattled, never pushing beyond smart limits.

In the end, Kilimanjaro wasn’t just a successful summit.

It was the clearest validation yet that when you build your approach around fitness, adaptation, and mindset, the mountain becomes less about suffering—and more about thriving.

Responses